The Check Digit Algorithm for NTU Matric Numbers

Yesterday, while checking my matriculation stuff, an idea crossed my mind – I already knew that the ending character of our matriculation number was a check digit, but I had never tried to find the algorithm for it. After having a look at several bridging numbers (matric numbers starting with ‘B’), the modulo 11 algorithm came into my mind. Then I decided to start doing the reverse engineering, which proved to be quite easy.

Let’s get started.

The Modulo 11 Algorithm

It is reasonable to guess that the check digit algorithm for our matric numbers shares the same pattern with that for the NRIC number / FIN, based on the following facts:

- The pattern of NTU matric numbers (e.g.

U2024197H) is similar to that of the Singapore NRIC number / FIN1; - On observing dozens of data, it can be noticed that the check digit ranges from

AtoLexcludingI(possibly because it is very visually similar to the number1), and that is a total of 11 possibilities. The case is the same for the NRIC number / FIN2.

That’s the modulo 11 algorithm. It’s a very common algorithm used to calculate check digits: it’s used in ISBN, the UK NHS number, the Chinese citizen ID number, etc.3 The reverse engineering is very straightforward, provided that the number of digits is not so large and that we have an adequate amount of sample data.

First, let’s assume that the algorithm for our matric numbers is indeed the modulo 11. Taking the above-mentioned matric number (U2024197H) as an example, the procedure for calculating the check digit using the modulo 11 algorithm is as follows:

- Put the 11 possible check digits in an ordered array

ALPHA[11]:ALPHA[11] = {'A', 'B', 'C', 'D', 'E', 'F', 'G', 'H', 'J', 'K', 'L'}. - Take out the numeric digits4 in the matric number, namely

d0tod6:{2, 0, 2, 4, 1, 9, 7}. - Assuming the weighting factors for the 7 digits (

d0tod6) arew0tow6respectively. Then multiply each digit with its corresponding weighting factor, and add them together:S = d0*w0 + d1*w1 + d2*w2 + d3*w3 + d4*w4 + d5*w5 + d6*w6. - Add an offset number

a, which may be any integer from 0 to 10, to produce the offset sumS_o(‘o’ denotes “offset”):S_o = S + a. - Divide the offset sum

S_oby 11, and get the remainderR:R = S_o % 11. - The check digit is just

ALPHA[R].

Attempting to Find the Weighting Coefficients and the Offset Number

Actually, I have done some Googling; I did find out that our senior, Daniel D. Zhang, had already done this using matric numbers obtained between 2010 and 2012, and here’s his post. However, as I tried to plug in some bridging numbers (the ones starting with ‘B’), I have found that although the set of weighting coefficients is still valid, the offset number is changed from 0 to 9. Furthermore, when I plugged in two or three undergrad matric numbers (starting with ‘U’), I have also found that the coefficients don’t work with them: two same remainders correspond to different check digits, which they shouldn’t.

It was then that I started to ponder whether it was because the algorithm had changed a bit for bridging students, and much for undergrads. But since the slightly-modified algorithm still worked on bridging numbers, I didn’t think that the algorithm (the pattern) has changed. Maybe it’s just the weighting coefficients. Then I started to do my own engineering.

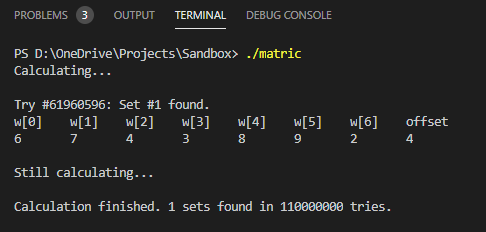

I collected quite a lot of undergrad matric numbers (A big thank you to those who have provided their matric numbers to me!), and I wrote a C program to attempt to find ALPHA[11]. (8 for loops, wow!) Then I did it. With a selected set of only 8 matric numbers, I got the only result out of 110,000,000 tries.

That wouldn’t be enough, for sure. I did a check using the rest of the matric numbers. To my surprise (well, maybe not really), it also worked!

Therefore, I think I can conclude that the weighting coefficients and the offset number is valid – at least for the matric numbers starting with ‘U’ and obtained from no earlier than 2018 (or possibly 2017). The former set of weighting coefficients worked for all undergrad matric numbers obtained before (and including) 2016, while my data, though mainly from my peers at Year 1 (obtained in 2020), include those obtained in 2019 and 2018 as well.

The three sets of weighting coefficients and the offset number are as follow:

For matric numbers starting with ‘U’, obtained before (and including) 2016 (“the former set”, calculated by Daniel D. Zhang):

w0 |

w1 |

w2 |

w3 |

w4 |

w5 |

w6 |

a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 8 | 0 |

For matric numbers starting with ‘U’, obtained after (and including) 2018:

w0 |

w1 |

w2 |

w3 |

w4 |

w5 |

w6 |

a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 9 | 2 | 4 |

For bridging numbers (matric numbers starting with ‘B’):

w0 |

w1 |

w2 |

w3 |

w4 |

w5 |

w6 |

a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 8 | 9 |

Due to the limitations of the sample data, matric numbers starting with ‘U’ and obtained in 2017 have not been studied. The data set should be the same as that in either 2016 or 2018.

And yes, that’s the check digit algorithm for our NTU matric numbers.

What’s next?

Having reverse-engineered the algorithm, I uploaded the reverse engineering program to GitHub in a new repository5. I have also written a webpage for quick validation and published it here. I will update it when I can improve it further, if I’m not too busy (or lazy).

-

Why not with the letter at the front? – Since we’re only studying two sets of data (namely the bridging numbers and the undergrad matric numbers), that doesn’t matter. If the letter is needed in the calculation, it can be easily found out. ↩

-

Of course, for privacy concerns, I have removed the actual data that I used, so only sample data is displayed. Nevertheless, the sample data provided in the source code can also lead to that only result. The example

U2024197Hused in this post is also a sample; it is not intentionally linked to anyone. ↩